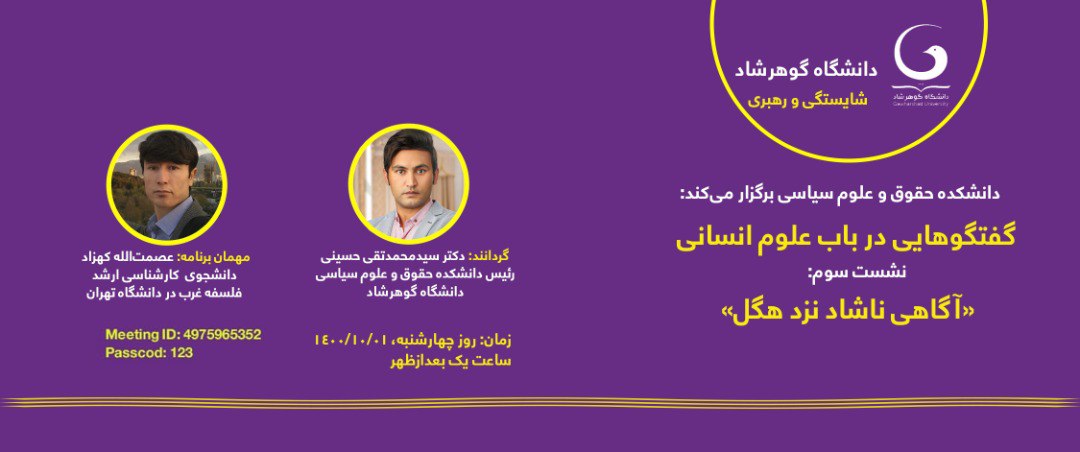

In the third session of the Conversations on Humanities series, we were honored to host Mr. Esmaeetollah Kazhazad, a master's student in Western Philosophy at the University of Tehran. He emphasized the importance of awareness in his discussion. According to Hegel, an idealistic and historicist German philosopher, in his influential work "Phenomenology of Spirit," he dedicated a chapter to "The Dissatisfaction of Consciousness." Consciousness, as a fundamental concept in German idealism, is often associated with dissatisfaction and suffering. Nietzsche also warned that awareness is intertwined with the deepest despair. But why? Why does dissatisfaction and pain resulting from awareness of existence find such a significant position within the philosophical system of idealism, especially among its prominent figures like Hegel? Idealism is a theoretical framework that aims to examine the world based on ideas about it rather than analyzing it as an object or a collection of objects. Idealism believes that the material world does not exist independently of the ideas one has about it in their mind. Therefore, "consciousness is the true foundation of reality," and it occupies a central position within this system.

What is Hegel's contribution to this story? What happens to the task of conscious dissatisfaction? Hegel, in the structure of the lofty and magnificent idealism, had a role; he said: unique ideas (or, to translate by Baqer Parham, "separate thoughts") can be combined and create an absolute idea. Hegel believed that not only is this possible and achievable, but it is also necessary; as Jean Wahl says, this methodology is related to the field of life, not just a method of pure speculation. Hegel insisted that we can truly know and understand a part of the dual world at that time and understand that we need to know and understand all of it. Hegel borrowed the concept of dialectic from Greece and Greek philosophy to reach a state where totality can be recognized and expanded. In the eyes of ancient philosophers like Socrates, dialectic was a method solely for exploring knowledge through a path full of questions and answers; as Tony Myers puts it, something similar to the famous game "20 Questions" where each question gets closer to the final answer through previous answers. We have often heard or read that Hegelian dialectic is a three-stage process. An initial thesis, first idea, or initiating proposition is proposed, then in an antithesis, it is criticized, modified, and ultimately negated. In the final step, these two are synthesized or blended into a more comprehensive idea; a process in which superior aspects are preserved while drawbacks and regressions are eliminated, resulting in an overall improvement. This image of Hegelian dialectic that we have heard or read everywhere is a common image in which different perspectives always have the ability to reconcile within a comprehensive truth and overcome obstacles; reconciliation of ideas and propositions is inherently what Walter Benjamin sees as the focal point in understanding Hegel.

But Hegel, as an influential and groundbreaking thinker, is more radical and uncompromising than this excellent and ordinary image of him and his ideas. The product of Hegelian dialectics is not reconciliation or agreement, but rather a deep understanding of the inherent contradiction in each thesis (or the ultimate divine unity).